Git demystified

How does git work internally?

This document is supposed to be a complete and concise guide to understand the mechanics of Git.

- This is a version controlled living document

- See its earlier versions at GitHub

- If you want to contribute, raise a Pull request

- Or file issues to report bugs/inconsistencies

Last edited on — Dec 22, 2019

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Basic commands

- Debugging

- Tools

- Personalization

- Workflows

- Releases

- Internals

- Extras

- Source

Introduction

Version Control Systems

Version control is a system that records changes to a file or set of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later. There are three types of version control systems:

- Local — LVCS has a simple database that locally keeps all the changes to files under revision control. e.g. RCS

- Centralized — CVCS has a single server that contains all the versioned files, and a number of clients that check out files from that central place. Clients don’t have all the history at a time. e.g. Subversion, Perforce

- Distributed — DVCS clients don’t just check out the latest snapshot of the files; rather, they fully mirror the repository, including its full history. Every clone is really a full backup of all the data. e.g. Git, Mercurial, Bazaar

History

In 2002, the Linux kernel project began using a proprietary DVCS called BitKeeper. In 2005, the relationship between the Linux community and the commercial company that developed BitKeeper broke down, and the tool’s free-of-charge status was revoked. Linus Torvalds (creator of Linux) began developing Git with the following goals —

- Speed

- Simple design

- Strong support for non-linear development (thousands of parallel branches)

- Fully distributed

- Able to handle large projects like the Linux kernel efficiently (speed and data size)

What is Git?

Git stores and thinks about information in a very different way, and understanding these differences will help you avoid becoming confused while using it.

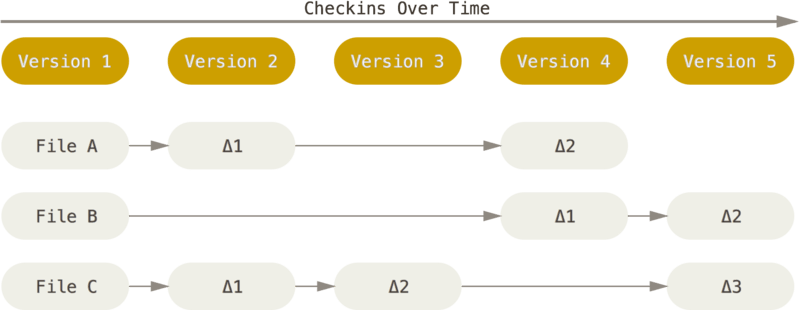

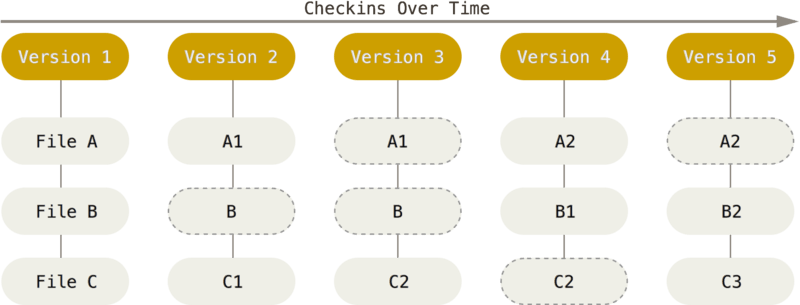

Snapshots, not Differences

Most VCSs store data as differences (deltas) over the previous versions.

However, Git thinks of its data more like a series of snapshots of a miniature filesystem. With Git, every time you commit, or save the state of your project, Git basically takes a picture of what all your files look like at that moment and stores a reference to that snapshot. To be efficient, if files have not changed, Git doesn’t store the file again, just a link to the previous identical file it has already stored. Git thinks about its data more like a stream of snapshots.

Nearly every operation is local

Most operations in Git need only local files and resources to operate. Generally no information is needed from another computer on your network. This also means that there is very little you can’t do if you’re offline. This may not seem like a huge deal, but you may be surprised what a big difference it can make.

Git has integrity

Everything in Git is checksummed before it is stored and is then referred to by that checksum. This means it’s impossible to change the contents of any file or directory without Git knowing about it. This functionality is built into Git at the lowest levels and is integral to its philosophy. You can’t lose information in transit or get file corruption without Git being able to detect it.

The mechanism that Git uses for this checksumming is called a SHA-1 hash. This is a 40-character string composed of hexadecimal characters (0–9 and a–f) and calculated based on the contents of a file or directory structure in Git.

Git generally only adds data

When you do actions in Git, nearly all of them only add data to the Git database. It is hard to get the system to do anything that is not undoable or to make it erase data in any way. This makes using Git a joy because we know we can experiment without the danger of severely screwing things up.

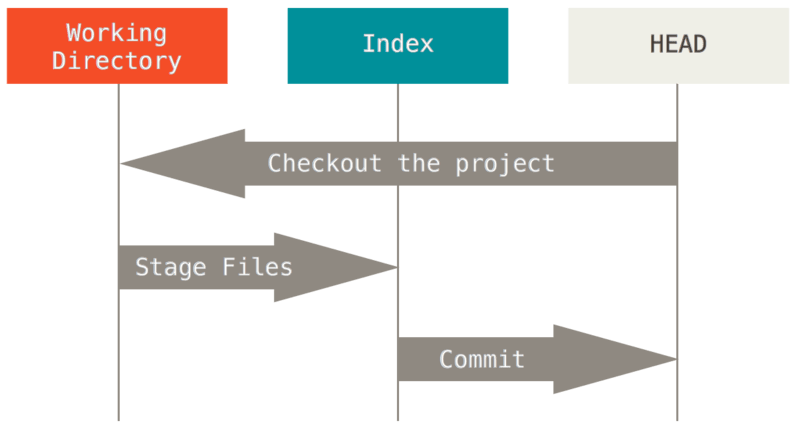

Manager of trees

Git is a manager of three different trees. By “tree” here, we really mean “collection of files”, not specifically the data structure. (There are a few cases where the index doesn’t exactly act like a tree, but for our purposes it is easier to think about it this way for now.)

HEAD- Last commit snapshot, next parent (commit database)Index- Proposed next commit snapshot (staging area)Working Directory- Sandbox

The first two trees store their content in an efficient but

inconvenient manner, inside the .git folder. The working directory

unpacks them into actual files, which makes it much easier for you

to edit them. Think of the working directory as a sandbox, where you

can try changes out before committing them to your staging area (index)

and then to history.

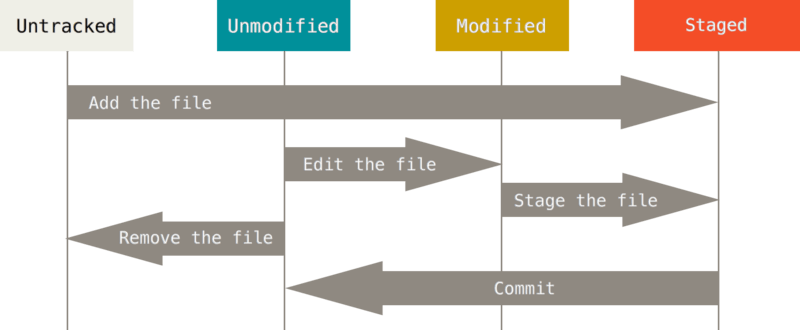

Each file in your working directory can be in one of two states:

tracked- Files that were in the last snapshot; they can beunmodified,modified, orstaged. In short, tracked files are files that Git knows about.untracked- Everything else — any files in your working directory that were not in your last snapshot and are not in your staging area.

When you first clone a repository, all of your files will be tracked and unmodified because Git just checked them out and you haven’t edited anything. As you edit files, Git sees them as modified, because you’ve changed them since your last commit. As you work, you selectively stage these modified files and then commit all those staged changes, and the cycle repeats.

There are three types of commits:

First commit- has no parentNormal commit- has 1 parentMerge commit- has 2 parents

Basic commands

Config

All the settings are stored in —

- System -

/etc/gitconfig - Global -

~/.gitconfigor~/.config/git/config - Local -

/path/to/repo/.git/config

Each level overrides values in the previous level, so values in

.git/config trump those in /etc/gitconfig.

# List all configs with source

# Git uses the last value for each unique key it sees in its output

git config --list --show-origin

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Set options

# Accepts --system, --global, --local(default)

# Name (required to use git)

git config --global user.name "John Doe"

# Email (required to use git)

git config --global user.email johndoe@example.com

# Editor

git config --global core.editor vim

# Commit template

# https://gist.github.com/adeekshith/cd4c95a064977cdc6c50

git config --global commit.template ~/.gitmessage.txt

# Pager (used in scrolling)

git config --global core.pager less

# GnuPG key (used in signing commits)

git config --global user.signingkey <gpg-key-id>

# Global gitignore

git config --global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_global

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Enable colors

git config --global color.ui true

# Meta diff - blue foreground, black background, and bold text

git config --global color.diff.meta "blue black bold"

# Other options

color.branch

color.diff

color.interactive

color.status

Help

# Detailed man page for config command

git help config

# Show concise options for config command

git config -h

Ignore

Often, you’ll have a class of files that you don’t want Git to

automatically add or even show as being untracked. These are generally

automatically generated files such as log files or files produced by

your build system. In such cases, you can create a file named

.gitignore at the project root and add patterns matching file

names/paths to ignore them.

The rules for the patterns to put in the .gitignore file are as follows:

- Blank lines or lines starting with

#are ignored - Standard glob patterns work, and will be applied recursively throughout the entire working tree

- You can start patterns with a forward slash

/to avoid recursivity - You can end patterns with a forward slash

/to specify a directory - You can negate a pattern by starting it with an exclamation point

!

Checkout GitHub’s suggested ignore patterns for different languages. https://github.com/github/gitignore

# See inside .gitignore

cat .gitignore

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Example patterns

# Ignore all .a files

*.a

# But do track lib.a, even though you're ignoring .a files above

!lib.a

# Only ignore the TODO file in the current directory, not subdir/TODO

/TODO

# Ignore all files in any directory named build

build/

# Ignore doc/notes.txt, but not doc/server/arch.txt

doc/*.txt

# Ignore all .pdf files in the doc/ directory and any of its

# subdirectories

doc/**/*.pdf

Init

# Initialize a git repo

# Run it at the project root

git init

# Clone an existing project

git clone https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# Clone project into a different directory

git clone https://github.com/musq/dotfiles ~/my-dotfiles

Status

See the status of files.

# Status

git status

# Short status

git status -s

Add

Move changes to index (staging area).

# Stage all files in the current directory

git add *

# or

git add .

# Stage files selectively

git add file1 dir1/file2 dir2

# Interactive add

# Use this to stage patches

git add -i

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Undo actions caused by the add command

# Unstage all files

git reset *

# Unstage all files in the current directory

git reset .

# Unstage files selectively

git reset file1 dir1/file2 dir2

# Detailed explanation of the reset command is presented

# later in a section below. Be sure to check it out.

Diff

# View differences for files in the working tree

# Supports selective files as arguments, similar to the add command

git diff

# View differences for files in the staging area

git diff --cached

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Algorithms

# https://stackoverflow.com/a/20199975

# Use a different algorithm to determine diff

# [options]

# - myers - (default) The basic greedy diff algorithm

# - minimal - Myers plus trying to minimize the patch size

# - patience - Attempts to trade readability of the patch versus

# patch size and processing time

# - histogram - Extends the patience algorithm to be faster and

# supports "low-occurrence common elements"

git diff --patience

# Set a diff algorithm globally

git config --global diff.algorithm histogram

Commit

# Commit staging area - Write commit message in an editor

git commit

# Commit staging area - Write commit message in command line

git commit -m "first commit"

# Commit staging area and sign it using GPG key

git commit -S -m "first commit"

# Commit all the changes: staging area + working tree

git commit -a -m "first commit"

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Ammend the last commit

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Rewriting-History#_git_amend

git commit --ammend -m "first commit - fix"

Move

# Rename a file

git mv file1 file2

# Move and rename a file

git mv file1 dir1/file2

Remove

# Remove file from staging area

# Supports selective files as arguments, similar to the add command

git rm file

# This file wouldn't be tracked from the next commit. Delete from

# working tree as well.

# Keep file in working tree, remove from staging area

git rm --cached file

# Force remove from staging area and delete from working tree

# DANGEROUS - It's a safety feature, don't use casually

git rm -f file

Log

# Show logs

git log

# Show only the last 4 commits

# Use any natural number you want

git log -4

# Also show the difference introduced in each commit

git log -p

# Show signatures

git log --show-signature

# Abbreviated stats (summary) for each commit

git log --stat

# Format the log

# [options] - oneline, short, full, fuller

git log --pretty=oneline

# Use custom format

# https://git-scm.com/docs/pretty-formats

git log --pretty=format:"%h - %an, %ar : %s"

# Display short commit SHA1 hash

git log --abbrev-commit

# If the first 7 chars are common between 2 commits, git will show

# 8 chars for both, 7 for the rest of them, to ensure uniqueness

# Shorthand for --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit

git log --oneline

# Show refs information

git log --decorate

# ASCII graph to show branch and merge history

git log --graph --oneline

# Don't display merge commits

git log --no-merges

# Show reflog information

git log -g

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Shortlog

git shortlog

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Filters

# https://git-scm.com/docs/git-log

# Filter by date

# [options] - since, until

git log --since 2.weeks.4.days.3.seconds

# Filter by authors

# Match (partial) either ashish or ranjan

git log --author ashish --author ranjan

# Search in commit messages

# Match (partial) either searchterm1 or searchterm2

git log --grep searchterm1 --grep searchterm2

# Pickaxe

# Find commits that added or removed a reference to 'searchterm'

git log -S searchterm

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# List differnces between refs (branches, tags, commits)

# List commits that are present in dev but not in master

# All of them are equivalent

git log master..dev

git log dev --not master

git log dev ^master

# The second/third method can be used to specify multiple branches

# List union of (dev1, dev2), remove commits in master

git log dev1 dev2 --not master

# List dev1, remove commits in union of (dev2, master)

git log dev1 ^dev2 ^master

# List the commits that are present

# - in dev but not in master, and

# - in master but not in dev

git log master...dev

# List the above changes with markers

git log master...dev --left-right

Grep

# https://git-scm.com/docs/git-grep

# Search for 'searchterm' in the git database

git grep searchterm

# Print line numbers

git grep -n searchterm

# Summarise search by only listing file name with the count of

# matches in each file

git grep -c searchterm

# Show the context of match by displaying the enclosing function

git grep -p searchterm

# Group searches by files

git grep --heading searchterm

Show

# Show details

# Accepts branch, tag, commit

git show a1b2c3d

# Show where your master was yesterday

# Accepts 2.weeks.1.day.8.hours.6.seconds

git show master@{yesterday}

# Parent of the HEAD (level-1)

git show HEAD^

# Second parent of the HEAD (for merge commits) (level-1)

# There can be a maximum of 2 parents for a commit

git show HEAD^2

# Parent of the HEAD (level-1)

git show HEAD~

# Grandparent of the HEAD with the first parent (level-2)

# Equivalent to git show HEAD^1~1

git show HEAD~2

# grandparent of the HEAD with the second parent (level-2)

git show HEAD^2~1

Clean

# Clean the working tree

# DANGEROUS - Removes untracked files

git clean

# Ignores files in .gitignore

# Dry run

git clean -n

# Remove subdirectories which become empty as a result of cleaning

git clean -d

# Safety feature to avoid deleting unsaved work

# Avoids submodules

git clean -f

# Clean the submodules as well

git clean -ff

# Remove all files, even which are present in .gitignore

git clean -x

# Interactive clean

git clean -i

Tags

# List tags

git tag

# List all the tags which match v1.8.*

git tag -l "v1.8.*"

# Create a lightweight tag named v1.9.2 from HEAD

git tag v1.9.2

# Create a lightweight tag named v1.9.2 from a1b2c3d

git tag v1.9.2 a1b2c3d

# Create annotated tag named v1.9.2 from HEAD

git tag -a v1.9.2 -m "First release"

# Create signed annotated tag named v1.9.2 from a1b2c3d

git tag -s v1.9.2 -m "First release" a1b2c3d

# Delete tag v1.9.2

git tag -d v1.9.2

# Verify tag v1.9.2 for a valid signature

git tag -v v1.9.2

Stash

# Stash the tracked modified files onto a stack

git stash

# Stash the untracked files as well

git stash -u

# Stash all the files, including the files specified in .gitignore

git stash -a

# Stash the changes but do not remove the changes from the staging area

# It will move the unstaged tracked files to stash

git stash --keep-index

# Equivalent to stash + apply --index

# Interactive stashing of patches

git stash --patch

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# List the stash stack

git stash list

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Apply the top of the stack to the working tree

git stash apply

# Run apply and stage the relevant changes as it were before the stash

git stash apply --index

# Drop the top entry of the stack

git stash drop

# Apply + Drop in one go

git stash pop

# Don't use it directly. Sometimes it will stop at apply due to merge

# conflicts. Stash hasn't been dropped yet, and you'll forget to

# manually drop it after resolving conflicts. And a few weeks down the

# line, when you run git stash pop again, it'll you give you conflicts

# Destash on a new branch

# Creates a new branch with the selected branch name, checks out the

# commit you were on when you stashed your work, reapplies your work

# there, and then drops the stash if it applies successfully

git stash branch <new branchname>

Remote

# List all the remotes

git remote -v

# Add a remote

git remote add musq https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# Change the remote URL

git remote set-url musq https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# Show detailed remote information

git remote show musq

# Rename a remote

git remote rename musq musq-dotfiles

# Remove a remote

git remote rm musq

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Set a default push to a remote

git config --local remote.pushDefault origin

Fetch

FETCH_HEAD records the branch which you fetched from a remote

repository with your last git fetch invocation.

# Fetch all branches from all remotes

git fetch

# Fetch all branches from upstream

git fetch upstream

# Fetch only master branch from upstream

git fetch upstream master

Pull

# If your current branch is set up to track a remote branch, fetch and

# then merge that remote branch into your current branch

git pull

# Fetch master branch from upstream and merge into current branch

git pull upstream master

# Pull changes and rebase current branch onto the FETCH_HEAD

git pull --rebase

# This is equivalent to the following 2 commands

git fetch

git rebase FETCH_HEAD

# See sections for Branch, Merge and Rebase below for detailed

# explanation of these commands

# NOTE - Avoid use of pull. Instead use fetch + merge individually

# It gives you more control over the steps

Push

# If your current branch is set up to track a remote branch, push

# changes from current branch to that remote branch

git push

# Only push master branch to origin/master

# Git expands it to git push origin refs/heads/master:refs/heads/master

git push origin master

# Force push dev branch on origin/dev

git push origin dev -f

# Push dev branch to serverfix

git push origin dev:serverfix

# Delete dev branch on origin

# Local dev branch will not be deleted

git push origin --delete dev

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Push tags

# Push tag v1.9.2 to origin

git push origin v1.9.2

# Push all tags to origin

git push origin --tags

# Delete tag v1.9.2 on the origin

git push origin --delete v1.9.2

Branch

Branches help you diverge from the main line of development and continue to do work without messing with that main line.

The way Git branches is incredibly lightweight, making branching operations nearly instantaneous, and switching back and forth between branches generally just as fast. Unlike many other VCSs, Git encourages workflows that branch and merge often, even multiple times in a day.

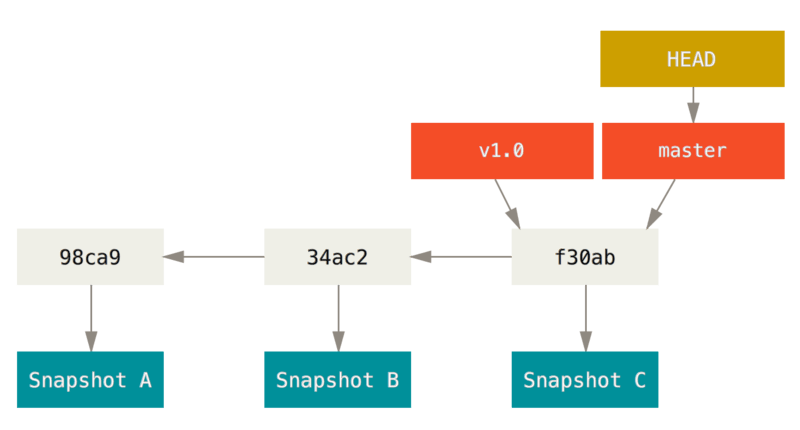

As mentioned in the History section, Git doesn’t store data as a series of changesets or differences, but instead as a series of snapshots. A commit is an immovable pointer to these snapshots and is based on of it’s parent commit. Thus changes are stored in a serial fashion chained to each other via commits.

A branch in Git is simply a lightweight movable pointer to a commit. The default branch name in Git is master. As you start making commits, you’re given a master branch that points to the last commit you made. Every time you commit, the master branch pointer moves forward automatically.

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Branching-Branches-in-a-Nutshell

# List all branches

git branch

# List all branches with detailed info

git branch -vv

# Create a new banch dev from the current branch

git branch dev

# Create a new banch dev from the master branch

git branch dev master

# Delete dev branch

# Safe to use - only deletes when the dev branch has been

# merged in the current branch

git branch -d dev

# Force delete dev branch

# DANGEROUS

git branch -D dev

# Show branches which have been merged into the current branch

git branch --merged

# Show branches which have been merged into the master branch

git branch --merged master

# Show branches which have not been merged into the current branch

git branch --no-merged

# Set tracking of current branch to origin/serverfix

git branch -u origin/serverfix

# Set tracking of master branch to origin/serverfix

git branch -u origin/serverfix master

Reset

Highly Recommended — https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Reset-Demystified

# master - w7x8y9z (current branch)

# dev - a1b2c3d

# Assume there are no modifications in any file

# i.e. at present, the output of `git status` is empty

# WD = Working Directory

# All of the following commands will move master to a1b2c3d

git reset --soft dev

# HEAD - changed (HEAD now points to a1b2c3d)

# Index - unchanged (All the changes between a1b2c3d & w7x8y9z are staged)

# WD - unchanged (Nothing is unstaged)

# Both these commands are equivalent

git reset --mixed dev

git reset dev

# HEAD - changed (HEAD now points to a1b2c3d)

# Index - changed (Nothing is staged)

# WD - unchanged (All the changes between a1b2c3d & w7x8y9z are unstaged)

git reset --hard dev

# HEAD - changed (HEAD now points to a1b2c3d)

# Index - changed (Nothing is staged)

# WD - changed (Sanitized. Output of git status would be empty)

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Reset with a path

# Unstage a file

git reset file

# Equivalent to `git reset HEAD file`

# HEAD - unchanged

# Index - changed (Nothing is staged in file)

# WD - changed (Everything is unstaged in file)

# --hard or --soft options cannot be used when argument is a file path

git reset a1b2c3d file

# HEAD - unchanged

# Index - changed (All the changes in file between a1b2c3d and HEAD are staged)

# WD - changed (Any remaining changes in file are unstaged)

Checkout

# Switch to dev branch

git checkout dev

# Create and switch to branch dev from the current branch

git checkout -b dev

# Create and switch to branch dev from the master branch

git checkout -b dev master

# Create a local branch from origin/serverfix and start tracking it

git checkout --track origin/serverfix

# Synonymous to the previous command only if the branch name (serverfix)

# you’re trying to checkout (a) doesn’t exist and (b) exactly matches

# a name on only one remote, Git will create a tracking branch for you

git checkout serverfix

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Checkout with file path

# Reset the file in the working tree to match the last commit

# DANGEROUS - Modifies the working tree (don't use casually)

git checkout file

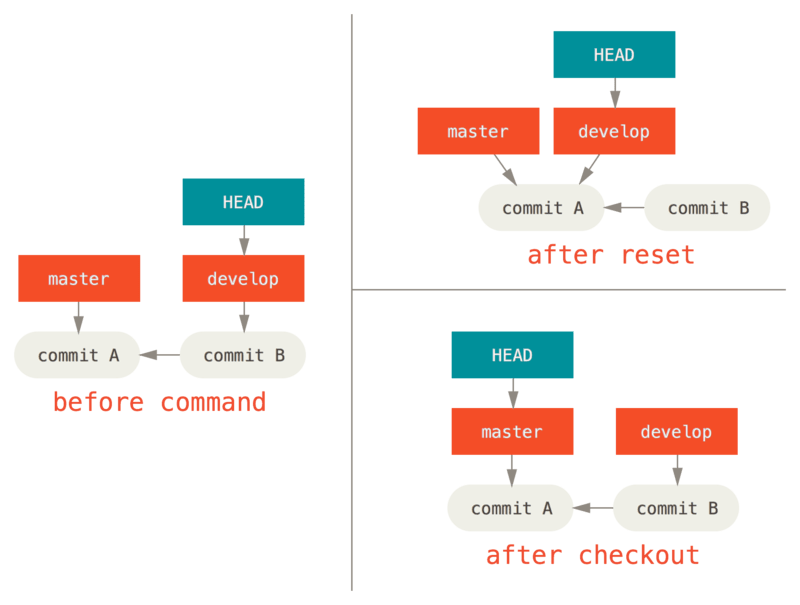

Reset vs Checkout

Follow the picture shown below.

commit A is the first commit. commit B is the second commit.

So, commit A is the parent of commit B. Now let’s run these two

commands separately and observe the changes they cause.

git reset master |

git checkout master |

|---|---|

| Move current ref to other ref | Move HEAD to other ref |

Reset moves the current reference to another tag, commit

Checkout moves the current HEAD to another branch, tag, commit

Here’s a cheat-sheet for which commands affect which trees. The “HEAD” column reads “REF” if that command moves the reference (branch) that HEAD points to, and “HEAD” if it moves HEAD itself. Pay especial attention to the WD Safe? column — if it says NO, take a second to think before running that command.

| HEAD | Index | Workdir | WD Safe? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commit Level | ||||

reset --soft [commit] |

REF | NO | NO | YES |

reset [commit] |

REF | YES | NO | YES |

reset --hard [commit] |

REF | YES | YES | NO |

checkout <commit> |

HEAD | YES | YES | YES |

| File Level | ||||

reset [commit] <paths> |

NO | YES | NO | YES |

checkout [commit] <paths> |

NO | YES | YES | NO |

Cherry Pick

# Cherry pick commit a1b2c3d in the current branch

git cherry-pick a1b2c3d

Revert

# Revert changes made by the commit a1b2c3d

# This is the compliment of cherry-pick

git revert a1b2c3d

Merge

MERGE_HEAD points to the head of the source branch that we are

merging into our destination branch.

ORIG_HEAD is created by commands that move your HEAD in a drastic

way, to record the position of the HEAD before their operation, so that

you can easily change the tip of the branch back to the state before

you ran them.

Fast Forward Merge happens when the source branch contains all of the

commits from the destination branch.

Note — A merge commit has 2 parents.

# Merge dev branch into current branch

git merge dev

# For all the files with conflicts select our version rather than theirs

# For all the files without conflicts merge both versions

# e.g. - Xours, Xtheirs

git merge -Xours dev

# Fake merge

# Merge dev into current branch, and shamelessly ignore the changes

# made in the dev branch

# e.g. - ours, theirs

git merge -s ours dev

# This can often be useful to basically trick Git into thinking that a

# branch is already merged when doing a merge later on. For example,

# say you branched off a release branch and have done some work on it

# that you will want to merge back into your master branch at some

# point. In the meantime some bugfix on master needs to be backported

# into your release branch. You can merge the bugfix branch into the

# release branch and also merge -s ours the same branch into your

# master branch (even though the fix is already there) so when you

# later merge the release branch again, there are no conflicts from the

# bugfix.

# Abort a merge

git merge --abort

# This might not work if you had unstashed, uncommitted changes in your

# working directory when you ran it

# Always stash before merging

# Reject merge if the commits in the remote branch are not signed

git merge --verify-signatures non-verify

# Merge if the commits in the remote branch are signed

git merge --verify-signatures signed-branch

# Merge and sign the resulting merge commit if the commits

# in the remote branch are signed

git merge --verify-signatures -S signed-branch

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Conflicts

# Re-Checkout the file again and replace the merge conflict markers

# Useful if you want to reset the markers and try to resolve them again

# e.g. - diff3 (for common ancestor file), merge (default)

git checkout --conflict=diff3 hello.rb

# List commits unique to HEAD, and MERGE_HEAD

git log --oneline --left-right HEAD...MERGE_HEAD

# List commits on either side of merge which are causing conflicts

git log --oneline --left-right --merge

# List common_ancestor..LO

git diff --ours

# List common_ancestor..RE

git diff --theirs

# Show how a merge conflict was resolved

git log --cc -p

# Check the patches in its output

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# List the SHA1 hashes of the git blobs of the files during merging

# Merging creates 3 files - common ancestor, LO (ours), RE (theirs)

git ls-files -u

# > 100644 8baef1b4abc478178b004d62031cf7fe6db6f903 1 hello.rb (common)

# > 100644 79dc3eeea3f4fb9bf81661dcff917ca4706c386f 2 hello.rb (ours)

# > 100644 cd470e619003f5e55999473fec485d85a8601e44 3 hello.rb (theirs)

# Access the contents of these blobs

git show :1:hello.rb > hello.common.rb

git show :2:hello.rb > hello.ours.rb

git show :3:hello.rb > hello.theirs.rb

# During a merge conflict on hello.rb, keep our version

# e.g. ours, theirs, union

git merge-file -p \

hello.ours.rb hello.common.rb hello.theirs.rb > hello.rb

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Combined diff format - How diff looks on resolving a conflict

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Advanced-Merging#_combined_diff_format

# Perils of reverting a merge commit using git revert

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Advanced-Merging#_reverse_commit

# Subtree merge

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Advanced-Merging#_subtree_merge

Rebase

git checkout serverfix

git rebase master

This operation works by going to the common ancestor of the two branches (the one you’re on (serverfix) and the one you’re rebasing onto (master)), getting the diff introduced by each commit of the branch you’re on, saving those diffs to temporary files, resetting the current branch to the same commit as the branch you are rebasing onto, and finally applying each change in turn.

When the rebase is complete, you can merge the serverfix branch on master.

git checkout master

git merge serverfix

It will be a fast-forward merge.

Interactive rebasing git rebase -i comes with the following options —

p, pick <commit>use commitr, reword <commit>use commit, but edit the commit messagee, edit <commit>use commit, but stop for amendings, squash <commit>use commit, but meld into previous commitf, fixup <commit>like “squash”, but discard this commit’s log messagex, exec <command>run command (the rest of the line) using shellb, breakstop here (continue rebase later with ‘git rebase –continue’)d, drop <commit>remove commitl, label <label>label current HEAD with a namet, reset <label>reset HEAD to a labelm, merge [-C <commit> | -c <commit>] <label> [# <oneline>]create a merge commit using the original merge commit’s message (or the oneline, if no original merge commit was specified). Use -c <commit> to reword the commit message.

Note — Always rebase your feature branch on the remote branch before opening a pull request.

# Interactive rebase

# Rewrite the last 3 commits

# HEAD~3 will not be modified beacuse it's the 4th commit

git rebase -i HEAD~3

# Rebase current branch on master

git rebase master

# Rebase dev branch on master

git rebase master dev

# If you face conflicts, resolve them and run

git rebase --continue

# Abort a rebase

git rebase --abort

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# More interesting rebases

# Rebase only client changes onto the master branch

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Branching-Rebasing#_more_interesting_rebases

git rebase --onto master server client

Rebase Hell

Always rebase your local branches. Never rebase any changes/commits which have been shared with other developers and they might have started working on top of it.

Otherwise, a special room shall be booked for thou in hell.

If you still do this montrosity, it’ll be very difficult to merge any changes and keep track of everything. It’ll be nothing less than a disaster.

Rebase vs Merge

Merge - If you want to record all the evidence of everything that

happened during the project development, go for merge. It’s a

historical document, valuable in its own right, and shouldn’t be

tampered with. From this angle, changing the commit history is almost

blasphemous; you’re lying about what actually transpired. So what if

there was a messy series of merge commits? That’s how it happened,

and the repository should preserve that for posterity.

Rebase - If you want to tell a story of how your project was made,

go for rebase. You wouldn’t publish the first draft of a book, and

the manual for how to maintain your software deserves careful editing.

This is the camp that uses tools like rebase and filter-branch to

tell the story in the way that’s best for future readers.

Submodules

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Submodules

Submodules allow you to keep a Git repository as a subdirectory of another Git repository. This lets you clone another repository into your project and keep your commits separate.

# Add a new submodule

# Creates a new entry in .gitmodules

git submodule add https://github.com/musq/git-park

# DO NOT use private URLs in submodules of public projects, because

# it might not be accessible to other people

# When cloning a repo, run these two to fetch the submodules' contents

# Initialize your local configuration file

git submodule init

# Fetch all the data from the submodules' repo and check out the

# appropriate commit listed in your superproject

git submodule update

# Or, run this one step instead

git clone --recurse-submodules https://github.com/musq/git-park

# Update all submodules

git submodule update --remote

# Update only the git-park submodule

git submodule update --remote git-park

# This command will by default assume that you want to update the

# checkout to the master branch of the submodule repository

# To change the default branch, set .gitmodules by running

git config -f .gitmodules submodule.git-park.branch serverfix

# This command updates the .gitmodules so that everyone tracks it

# If you want to keep these changes local, store in the .git/config file

git config submodule.git-park.branch serverfix

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# List the commits introduced in submodules as difference

git diff --submodule

# Set global config

git config --global diff.submodule log

# Set config to view changes in git status

git config status.submodulesummary 1

# See submodule changes in git log

git log -p --submodule

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Working on a submodule

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Submodules#_working_on_a_submodule

# If you have made changes in your submodules locally

# (committed or uncommitted), run

# Merge your changes with remote that was set up for this submodule

git submodule update --remote --merge

# Rebase your changes with remote that was set up for this submodule

git submodule update --remote --rebase

# Update without merging

git submodule update --remote

# Running this will update the submodule to whatever is on the server

# and reset your project to a detached HEAD state.

# If you have committed changes in submodules, then you can simply go

# back into the directory and check out your branch again (which will

# still contain your work) and merge or rebase origin/stable (or

# whatever remote branch you want) manually.

# If you haven’t committed your changes in your submodule and you run

# a submodule update that would cause issues, Git will fetch the

# changes but not overwrite unsaved work in your submodule directory.

# If you made changes that conflict with something changed upstream,

# Git will let you know when you run the update.

# You can go into the submodule directory and fix the conflict just as

# you normally would.

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Push submodule changes

# Fail superproject push if any of the committed submodule

# changes hasn't been pushed

git push --recurse-submodules=check

# Push all the submodule changes to their remotes before

# pushing superproject

git push --recurse-submodules=on-demand

# Set git to ask you if you want to push the submodule changes

# when you're pushing the superproject

# e.g. check, on-demand

git config push.recurseSubmodules check

# Merge submodule changes conflict

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Submodules#_merging_submodule_changes

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Submodule foreach

git submodule foreach 'git fetch && git merge origin/master'

# Get difference of superproject and all its submodules

git diff; git submodule foreach 'git diff'

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Submodule aliases

git config alias.sdiff '!'"git diff && git submodule foreach 'git diff'"

git config alias.spush 'push --recurse-submodules=on-demand'

git config alias.supdate 'submodule update --remote --merge'

# Submodule issues

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Submodules#_issues_with_submodules

Debugging

Blame

List the commits that last modified each line in a file.

Ocassionally when you’re tracking a bug, you’ll close in on a line in a file as the source of the bug. In this case Blame helps by telling you which commit last modified this line and possibly introduced the bug.

# List committers of Makefile from line 69-82

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Debugging-with-Git#_file_annotation

git blame -L 69,82 Makefile

# If any line in its output begins with ^ (e.g. ^a1b2c3d), it

# means these lines haven't changed since their first commit

# List the context as well

# Git analyzes the file you’re annotating and tries to figure out where

# snippets of code within it originally came from if they were copied

# from elsewhere

git blame -C -L 69,82 Makefile

Bisect

Find the commit that introduced a bug, using a binary search.

Run git bisect start to begin bisecting. Tell git about a commit that

definitely contains the bug using git bisect bad bad-commit. Then

tell git about a commit that definitely does not contain the bug using

git bisect good good-commit. Git will reset you HEAD to the middle

of these two commits (binary search). Run your tests and determine if

the bug exists at this point. If it does, tell git using

git bisect bad, otherwise do git bisect good. Git will then reset

the HEAD to the middle of the next set of bad and good commits. You’ll

iterate these steps till Git reaches the final suspected commit. At the

end, Git will tell you which commit introduced the bug.

Don’t forget to exit bisect mode by running git bisect reset when

it’s over.

# Begin bisecting

git bisect start

# We know for certain that commit a1b2c3d contains the bug

git bisect bad a1b2c3d

# We know for certain that tag v1.9.2 doesn't contain the bug

git bisect good v1.9.2

# For each iteration, tell git if the bug is present or not

git bisect good

# or

git bisect bad

# When you're finished, reset your HEAD by

git bisect reset

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# To automate this using a script

git bisect start bad-commit good-commit

git bisect run test-error.sh

# test-error.sh must be set up to return exit 0 on success,

# and non-zero on fail

Tools

Git Desktop

# View git logs in a desktop app, comes pre-installed with git

gitk

Git GUI

# Write commit messages in a Graphical User Interface

git gui

Git Web

# View git logs in browser

git instaweb --httpd=webrick

Credentials

# Enable caching of credentials

git config --global credential.helper cache

# Set file to which credentials should be stored

git config --global credential.helper 'store --file ~/.git-credentials'

# Set timeout to 1 hour

git config --global credential.helper 'cache --timeout 3600'

# How it works

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Credential-Storage#_under_the_hood

Rerere (reuse recorded resolution)

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Rerere

# When rerere is enabled, Git will keep a set of pre- and post-images

# from successful merges, and if it notices that there’s a conflict

# that looks exactly like one you’ve already fixed, it’ll just use

# the fix from last time, without bothering you with it.

# Enable rerere in config

git config --global rerere.enabled true

Reflog

Git silently records what your HEAD is every time you change it.

Each time you commit or change branches, the reflog is updated

using the git update-ref command.

All the contents are stored in .git/logs/*

# A log of where your HEAD and branch references have been for the

# last few months

# This is stored locally, and not synced on remote

git reflog

Filter-branch

Rewrite history in bulk.

# Remove the password.txt file from all the commits

git filter-branch --tree-filter 'rm -f passwords.txt' HEAD

# Change email in git commits

git filter-branch --commit-filter '

if [ "$GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL" = "ashish@localhost" ];

then

GIT_AUTHOR_NAME="Ashish Ranjan";

GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL="ashish@example.com";

git commit-tree "$@";

else

git commit-tree "$@";

fi' HEAD

Bundle

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Bundling

Replace

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Replace

Rev parse

# Show the commit hash of master branch

git rev-parse master

# > d81dc9b1f83cccec24e12113aa471b736cd14d29

Personalization

Attributes

Some of the config settings can also be specified for a path, so that

Git applies those settings only for a subdirectory or subset of files.

These path-specific settings are called Git attributes and are set

either in a .gitattributes file in one of your directories (normally

the root of your project) or in the .git/info/attributes file if you

don’t want the attributes file committed with your project.

# Treat *.dat files as binary

# Git will not try to compute or print a diff for changes in this file

# when you run git show or git diff

*.dat binary

# Use gpg to run diff on gpg files

*.gpg diff=gpg

# Run diff on png files with the exif option in gitconfig

*.png diff=exif

# Specify the exiftool for exif data

git config diff.exif.textconv exiftool

# Ignore test directory on exporting the project as archive

test/ export-ignore

# On merging, use our version of database.xml

database.xml merge=ours

# Define a dummy ours strategy

git config --global merge.ours.driver true

Refspec

Reference specifications can help you harness the full power of remotes.

When you add a new remote, it is stored in .git/config.

The format of the refspec is, first, an optional +, followed by

<src>:<dst>, where <src> is the pattern for references on the

remote side and <dst> is where those references will be tracked

locally. The + tells Git to update the reference even if it isn’t

a fast-forward.

# See what's inside .git/config

# > [remote "origin"]

# > url = https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# > fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

# List commits in origin/master

git log origin/master

git log remotes/origin/master

git log refs/remotes/origin/master

# They’re all equivalent, because Git expands each of them to

# refs/remotes/origin/master.

# Partial globs are invalid in refspec

# The following is invalid

fetch = +refs/heads/qa*:refs/remotes/origin/qa*

# However, namespaces are allowed

# The following is valid

fetch = +refs/heads/qa/*:refs/remotes/origin/qa/*

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Push refspec

# Consider a project with the following in .git/config. There are two

# local branches - master, dev.

# > [remote "origin"]

# > url = https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# > fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

# > push = refs/heads/dev:refs/heads/qa/dev-o

# >

# > [remote "upstream"]

# > url = https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# > fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/upstream/*

# > push = refs/heads/dev:refs/heads/qa/dev-u

# There are two push refspecs defined for refs/heads/dev.

# Consider the following two situations (you're on master) -

git push origin master # pushes local master branch to origin/master

git push # (NOT SURE) most probably pushes to the first matching refspec

git push origin dev # pushes local dev branch to origin/qa/dev-o

git push upstream dev # pushes local dev branch to upstream/qa/dev-u

Hooks

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Customizing-Git-Git-Hooks

Git has a way to fire off custom scripts when certain important actions

occur. There are two groups of these hooks: client-side and

server-side. Client-side hooks are triggered by operations such as

committing and merging, while server-side hooks run on network

operations such as receiving pushed commits. There are following types

of client hooks —

Commit hooks

-

pre-commit- Runs before you even type in a commit message. It’s used to inspect the snapshot that’s about to be committed, to see if you’ve forgotten something, to make sure tests run, or to examine whatever you need to inspect in the code. -

prepare-commit-msg- Runs before the commit message editor is fired up but after the default message is created. It lets you edit the default message before the commit author sees it. -

commit-msg- Takes one parameter, which again is the path to a temporary file that contains the commit message written by the developer. You can use it to validate your project state or commit message before allowing a commit to go through. -

post-commit- Runs After the entire commit process is completed. Generally, this script is used for notification or something similar.

Email hooks

-

pre-applypatch- Runs after the patch is applied but before a commit is made, so you can use it to inspect the snapshot before making the commit. You can run tests or otherwise inspect the working tree with this script. -

applypatch-msg- Takes a single argument: the name of the temporary file that contains the proposed commit message. use this to make sure a commit message is properly formatted, or to normalize the message by having the script edit it in place. -

post-applypatch- Runs after the commit is made. You can use it to notify a group or the author of the patch you pulled in that you’ve done so. You can’t stop the patching process with this script.

Other hooks

-

pre-rebase- Runs before you rebase anything and can halt the process by exiting non-zero. You can use this hook to disallow rebasing any commits that have already been pushed. -

post-rewrite- Run by commands that replace commits, such as git commit –amend and git rebase (though not by git filter-branch). Its single argument is which command triggered the rewrite, and it receives a list of rewrites on stdin. This hook has many of the same uses as the post-checkout and post-merge hooks. -

post-checkout- Runs after a successful git checkout. you can use it to set up your working directory properly for your project environment. This may mean moving in large binary files that you don’t want source controlled, auto-generating documentation, or something along those lines. -

post-merge- Runs after a successful merge command. You can use it to restore data in the working tree that Git can’t track, such as permissions data. This hook can likewise validate the presence of files external to Git control that you may want copied in when the working tree changes. -

pre-push- Runs during git push, after the remote refs have been updated but before any objects have been transferred. It receives the name and location of the remote as parameters, and a list of to-be-updated refs through stdin. You can use it to validate a set of ref updates before a push occurs (a non-zero exit code will abort the push). -

pre-auto-gc- Invoked just before the garbage collection takes place, and can be used to notify you that this is happening, or to abort the collection if now isn’t a good time.

Workflows

Git makes it extremely easy to merge changes from multiple developers. This can be made even more convenient by following a project specific standard for both types of users:

- Contributors

- Owners/Maintainers

Contributors

As a contributor, you must follow the contributing guidelines (e.g.

Contributing.md) as mentioned in the corresponding projects. If you

can’t find any such guidelines for the project, please follow these:

- Use conventional-commits to format commit messages

- Never commit trailing whitespaces

- Don’t keep an empty line at the end of your file

- Always rebase your branch on target branch before creating a Pull Request

Generate pull request template

git request-pull [-p] <start> <url> [<end>]

The git request-pull command takes the base branch

This summary can be emailed to the owner of the upstream repo.

Note — This command does not modify anything.

# Generate a request asking your upstream project to pull changes into

# their tree. The request, printed to the standard output, begins with

# the branch description, summarizes the changes and indicates from

# where they can be pulled.

# The upstream project is expected to have the commit named by <start>

# and the output asks it to integrate the changes you made since that

# commit, up to the commit named by <end>, by visiting the repository

# named by <url>.

git request-pull upstream/master https://github.com/musq/dotfiles dev

# upstream/master - upstream branch

# dev - local development branch

# There must be a branch named dev on the repo in the provided URL,

# and it must be identical to your local dev branch

Send commit patches via email

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Contributing-to-a-Project#_project_over_email

# Generate patches from commits since upstream/master upto

# current branch

git format-patch -M upstream/master

# The format-patch command prints out the names of the patch files it

# creates.

# The -M switch tells Git to look for renames.

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Set up IMAP in .git/config

[imap]

folder = "[Gmail]/Drafts"

host = imaps://imap.gmail.com

user = user@gmail.com

pass = YX]8g76G_2^sFbd

port = 993

sslverify = false

# If your IMAP server doesn’t use SSL, the last two lines probably

# aren’t necessary, and the host value will be imap:// instead of

# imaps://. When that is set up, you can use git imap-send to place

# the patch series in the Drafts folder of the specified IMAP server:

cat *.patch | git imap-send

# At this point, you should be able to go to your Drafts folder,

# change the To field to the mailing list you’re sending the patch to,

# possibly CC the maintainer or person responsible for that section,

# and send it off.

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# You can also send the patches through an SMTP server.

# Set up sendmail SMTP in .git/config

[sendemail]

smtpencryption = tls

smtpserver = smtp.gmail.com

smtpuser = user@gmail.com

smtpserverport = 587

# After this is done, you can use git send-email to send your patches:

git send-email *.patch

# It will now ask you to provide the recipient of this email

Create pull requests on GitHub

You can use GitHub web user interface to create and manage pull requests.

GitHub pull requests are essentially issues.

-

https://github.com/musq/dotfiles/pull/6 redirects to https://github.com/musq/dotfiles/issues/6

-

https://github.com/musq/dotfiles/issues/21 redirects to https://github.com/musq/dotfiles/pull/21

You can reference other issues/pull-request by their number on a GitHub pull request page using:

#<num>- refer to issue in the current repositoryusername#<num>- refer to issue in a fork of this repositoryusername/repo#<num>- refer to issue in another repository

Owners/Maintainers

- Always make sure your project has a license as the first commit before any other code

Whether you maintain a canonical repository or want to help by verifying or approving patches, you need to know how to accept work in a way that is the clearest for other contributors and sustainable by you over the long run. This can consist of accepting and applying patches emailed to you, or integrating changes in remote branches for repositories you’ve added as remotes to your project.

You should choose one of the following workflows:

-

Centralized- One central hub, or repository, can accept code, and everyone synchronizes their work with it. A number of developers (all have push access to this repo) are nodes, and synchronize their changes with it. -

Integration-Manager- One user (owner) with push access. Other contributors fork the upstream repo, make changes, and create a pull request (PR) for their changes. The owner can merge/reject this PR. -

Dictator and Lieutenants- Multiple integration managers (lieutenants) are in charge of certain parts of repository. They review PRs for their teritorry. All the lieutenants have one integration manager known as the benevolent dictator (BD). The dictator merges all these changes into his master branch from which other collaborators must pull. The dictator has the final say for which features will go in which release. Useful for very big public repositories. e.g. Linus Torvalds is BD of linux kernel, Bram Moolenaar is BD of vim

Merge patches from email

# Check if a patch applies cleanly before actually applying it

git apply --check 0001-first-commit.patch

# Apply the patch

git apply 0001-first-commit.patch

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Apply a series of patches from a mailbox

# If someone has emailed you the patch properly using git send-email,

# and you download that into an mbox format, then you can point git am

# to that mbox file, and it will start applying all the patches it sees.

# If you run a mail client that can save several emails out in mbox

# format, you can save entire patch series into a file and then use

# git am to apply them one at a time.

git am

# Apply a patch using am (apply-mail)

git am 0001-first-commit.patch

# Tell git-am to merge smartly using a three-way-merge

git am -3 0001-first-commit.patch

Merge pull requests on GitHub

Go to the page of the pull request on GitHub, and merge it using the

green Merge button.

Merge GitHub pull requests locally —

1. Using pull request patches

# This will directly merge the patch into the current branch

curl https://github.com/musq/dotfiles/pull/21.patch | git am

2. Using pull request refs

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/GitHub-Maintaining-a-Project#_pr_refs

# List all the raw references on the remote

git ls-remote https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# > 10d539600d86723087810ec636870a504f4fee4d HEAD

# > 10d539600d86723087810ec636870a504f4fee4d refs/heads/master

# > 6a83107c62950be9453aac297bb0193fd743cd6e refs/pull/1/head

# > afe83c2d1a70674c9505cc1d8b7d380d5e076ed3 refs/pull/1/merge

# > 3c8d735ee16296c242be7a9742ebfbc2665adec1 refs/pull/2/head

# > 15c9f4f80973a2758462ab2066b6ad9fe8dcf03d refs/pull/2/merge

# > a5a7751a33b7e86c5e9bb07b26001bb17d775d1a refs/pull/4/head

# > 31a45fc257e8433c8d8804e3e848cf61c9d3166c refs/pull/4/merge

# refs/pull/*/head - The forked branch from which this PR came

# refs/pull/*/merge - What the current branch would look like after

# hitting the merge button

# Add the repo as origin, then hit

git fetch origin refs/pull/2/head

# This tells Git, “Connect to the origin remote, and download the ref

# named refs/pull/2/head.” Git happily obeys, and downloads everything

# you need to construct that ref, and puts a pointer to the commit you

# want under .git/FETCH_HEAD. You can follow that up with git merge

# FETCH_HEAD into a branch you want to test it in, but that merge

# commit message looks a bit weird. Also, if you’re reviewing a lot of

# pull requests, this gets tedious.

# Modify .git/config

# > [remote "origin"]

# > url = https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

# > fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

# > fetch = +refs/pull/*/head:refs/remotes/origin/pr/*

# That last line tells Git, "All the refs that look like

# refs/pull/123/head should be stored locally like

# refs/remotes/origin/pr/123."

# Now do a git fetch

git fetch

# > # …

# > * [new ref] refs/pull/1/head -> origin/pr/1

# > * [new ref] refs/pull/2/head -> origin/pr/2

# > * [new ref] refs/pull/4/head -> origin/pr/4

# > # …

# Create branch pr/2 from origin/pr/2 and begin tracking it

git checkout pr/2

# Optionally rebase it onto master branch

git rebase master

# Merge it with master

git checkout master

git merge pr/2

Releases

Semantic versioning

Follow semantic versioning scheme for your releases.

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

MAJORversion when you make incompatible API changesMINORversion when you add functionality in a backwards-compatible mannerPATCHversion when you make backwards-compatible bug fixes.

Additional labels for pre-release and build metadata are available as

extensions to the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format.

Generate Build number

# Generate a build number

git describe master

# > v1.6.2-rc1-20-g8c5b85c

# In response, Git generates a string consisting of the name of the

# most recent tag earlier than that commit, followed by the number

# of commits since that tag, followed finally by a partial SHA-1

# value of the commit being described (prefixed with the letter "g"

# meaning Git)

Prepare Assets

# For gzip files

git archive master --prefix='project/' | gzip > `git describe master`.tar.gz

# It generates a file named like: v1.6.2-rc1-20-g8c5b85c.tar.gz

# For zip files

git archive master --prefix='project/' --format=zip > `git describe master`.zip

GPG public key as tag

If you do sign your tags, you may have the problem of distributing the public GPG key used to sign your tags. You can solve this issue by including your public key as a blob in the repository and then adding a tag that points directly to that content.

# Find out the fingerprint of the key used to sign your tags/commits

gpg --list-keys

# The desired key - 013B49A9

# Export the key as blob

gpg --armor --export 013B49A9 | git hash-object -w --stdin

# > 659ef79kd181633c87ec71ac3f9ba29fe5775b92

# Tag this blob object

git tag -a musq-pgp-pub 659ef79kd181633c87ec71ac3f9ba29fe5775b92

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Import key

# Clone this project and import key from this tag

git show musq-pgp-pub | gpg --import

Internals

When you run git init in a new or existing directory, Git creates

the .git directory, which is where almost everything that Git stores

and manipulates is located. If you want to back up or clone your

repository, copying this single directory elsewhere gives you nearly

everything you need. Let’s check what’s inside this —

ls -la .git

COMMIT_EDITMSGfile is created when you rungit commit. It opens your EDITOR program to edit this file. When your editor exits, it reads the file and saves it as the message for the commit.configfile contains your project-specific configuration optionsdescriptionfile is used only by the GitWeb program, so don’t worry about itFETCH_HEADfile records the branch which you fetched from a remoteHEADfile points to the branch you currently have checked outhooksdirectory contains your client- or server-side hook scriptsindexfile is where Git stores your staging area informationinfofile keeps a global exclude file for ignored patterns that you don’t want to track in a .gitignore filelogsdirectory contains the reflog informationMERGE_HEADfile points to the head of the source branch that we are merging into our destination branch.objectsdirectory stores all the content for your databaseORIG_HEADfile is created by commands that move your HEAD in a drastic way, to record the position of the HEAD before their operation, so that you can easily change the tip of the branch back to the state before you ran them.packed-refsfile contains the refs in packed formrefsdirectory stores pointers into commit objects in that data (branches, tags, remotes and more)

Objects

Highly Recommended — https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Git-Objects

There are four types of objects in git:

blob- snapshots of individual files stored in files with names as the resulting SHA1 hashtree- contains pointers to blobscommit- contains pointers to blobs and treestag- (only for annotated tags) contains pointer to a commit

# Write data to an blob object

# -w tells it to write the data in the database

echo 'abc xyz' | git hash-object -w --stdin

# > 08c25e8dc5322b84902fbd98d0adbd33c0211ce8

# The output from the above command is a 40-character checksum hash

# This is the SHA-1 hash — a checksum of the content you’re storing

# plus a header

# Blob object is stored in

# .git/objects/08/c25e8dc5322b84902fbd98d0adbd33c0211ce8

# The first 2 chars are used as the directory name

# The other 38 chars are used as file name

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Read object contents

git cat-file -p 08c25e8dc5322b84902fbd98d0adbd33c0211ce8

# > abc xyz

# Read object type

git cat-file -t 08c25e8dc5322b84902fbd98d0adbd33c0211ce8

# > blob

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Further reading about tree and commit objects at

# https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Git-Objects

References

A reference is simple memorable name that acts as an alias for a commit,

so that it is easier to access that commit.

References are actually the names of files stored in .git/refs which

contain the commit SHA-1 to which they are aliased.

# Manually change the pointer of master branch

echo 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9 > .git/refs/heads/master

# This does the same thing, but it's safer

# It's what git uses on git checkout <branch>

git update-ref refs/heads/master 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9

# Create a branch on the given commit

git update-ref refs/heads/dev a1b2c3d

# Create a lightweight tag (non annotated)

git update-ref refs/tags/v1.9.2 cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d

# Note - If you create an annotated tag, Git creates a tag object

# and then writes a reference to point to it rather than directly

# to the commit.

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# See what's inside .git/HEAD file

cat .git/HEAD

# > ref: refs/heads/master

# Safely read content of HEAD, same thing as above

git symbolic-ref HEAD

# Safely set the new value of HEAD

git symbolic-ref HEAD refs/heads/dev

Remote refs

Remote references differ from branches (refs/heads references) mainly in that they’re considered read-only. Git manages them as bookmarks to the last known state of where those branches were on those servers.

# See what's inside a remote ref

cat .git/refs/remotes/origin/master

# > ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949

Packfiles

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Packfiles

Git optimizes its datastore by removing redundant blob objects and

packing everything up in packfiles *.pack and indexes *.idx. These

reside in .git/objects/pack/.

This is done on running garbage collector git gc, or pushing changes

git push.

Garbage collection

# Run soft garbage collection

git gc --auto

# This generally does nothing. You must have around 7,000 loose objects

# or more than 50 packfiles for Git to fire up a real gc command.

# Modify these limits with the gc.auto and gc.autopacklimit

# config settings, respectively.

# - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

# Also packs up references (.git/refs/*) into a single file

# named .git/packed-refs

# If you update a reference, Git doesn’t edit this file but instead

# writes a new file to refs/heads. To get the appropriate SHA-1 for a

# given reference, Git checks for that reference in the refs directory

# and then checks the packed-refs file as a fallback. However, if you

# can’t find a reference in the refs directory, it’s probably in your

# packed-refs file.

# See what's inside .git/packed-refs

cat .git/packed-refs

# > # pack-refs with: peeled fully-peeled

# > cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d refs/heads/experiment

# > ab1afef80fac8e34258ff41fc1b867c702daa24b refs/heads/master

# > cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d refs/tags/v1.0

# > 9585191f37f7b0fb9444f35a9bf50de191beadc2 refs/tags/v1.1

# > ^1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9

# Notice the last line of the file, which begins with a ^. This means

# the tag directly above is an annotated tag and that line is the

# commit that the annotated tag points to.

Fsck

If you delete reflog using rm -Rf .git/logs/, us can still recover

your commits using git fsck.

# Shows all objects that aren’t pointed to by another object

git fsck --full

# > Checking object directories: 100% (256/256), done.

# > Checking objects: 100% (18/18), done.

# > dangling blob d670460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4

# > dangling commit ab1afef80fac8e34258ff41fc1b867c702daa24b

# > dangling tree aea790b9a58f6cf6f2804eeac9f0abbe9631e4c9

# > dangling blob 7108f7ecb345ee9d0084193f147cdad4d2998293

# In this case, you can see your missing commit after the string

# "dangling commit". You can recover it the same way, by adding

# a branch that points to that SHA-1.

Removing objects

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Maintenance-and-Data-Recovery#_removing_objects

If someone at any point in the history of your project added a single huge file, every clone for all time will be forced to download that large file, even if it was removed from the project in the very next commit. Because it’s reachable from the history, it will always be there. Git can be instructed to remove such objects.

Be warned: this technique is destructive to your commit history.

It rewrites every commit object since the earliest tree you have to modify to remove a large file reference. If you do this immediately after an import, before anyone has started to base work on the commit, you’re fine – otherwise, you have to notify all contributors that they must rebase their work onto your new commits.

Environment variables

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Environment-Variables

Git always runs inside a bash shell, and uses a number of shell environment variables to determine how it behaves. It comes in handy to know what these are, and how they can be used to make Git behave the way you want it to.

Extras

Bash/Zsh helpers

-

git-completion.bash- [source] Support completion of options -

git-prompt.sh- [source] Show repository status in prompt

Usage instructions are provided inside each script.

Bare Repo

A bare repository does not have a working tree. It only has commit database. I’m not sure about the staging area, though. It is the recommended way to set up Git on a server from which users will only interact by pushing/pulling and will never need to checkout a working tree there.

# Initialize a bare repo

git init --bare

# Clone another repo as a bare repo

git clone --bare https://github.com/musq/dotfiles

Git on a server

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/GitHub-Account-Setup-and-Configuration

A Git repo can be served using any of the these protocols:

HTTPS- For public anonymous users. Unauthenticated, Secure.SSH- For authenticated users. Authenticated, SecureGIT- Unauthenticated, Insecure.

To set up SSH, create a user named git, and add your users public

ssh keys in this users .ssh/authorized_keys file. That way, you’d only

need to create a single user on your server for SSH purposes.

You can easily restrict the git user account to only Git-related

activities with a limited shell tool called git-shell that comes with

Git. If you set this as the git user account’s login shell, then that

account can’t have normal shell access to your server. To use this,

specify git-shell instead of bash or csh for that account’s

login shell.

sudo chsh git -s $(which git-shell)

Scripting GitHub

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/GitHub-Scripting-GitHub

Use the GitHub hooks system and its API to make GitHub work how you want it to.

Source

Pro Git — Scott Chacon and Ben Straub